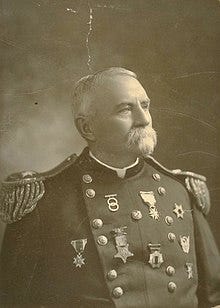

Harrison Gray Otis

On October 29, 1901, Mrs. M. Leavitt met with Publisher Harrison Gray Otis at the Times to complain that she was misquoted in “Outrages at Point Loma,” which the paper had published a day earlier. Otis, 65, often barked demands from his office that echoed throughout the newsroom. The paper, with a circulation of 29,000, had thrived under his leadership. Otis railed against Democrats (“hags, harlots and pollutants”) and organized labor (“skunks, gas-pipe ruffians and anarchists”). He ran the Los Angeles Times and the weekly L.A. Mirror with two mottos: “People want their names in the paper” and “Everybody likes to see somebody else kicked, preferably below the belt.” But he was deferential, if not apologetic, to Mrs. Leavitt.

Mrs. Leavitt told Otis that his reporter, Lanier Bartlett, had misunderstood her. She had been quoted as saying that women were being starved and treated like convicts and that “gross immoralities” were being practiced in the Theosophical Society’s utopian community at Point Loma. Everything she had told him, Mrs. Leavitt said, was based on gossip and accounts she had read in other newspapers, not on any first-hand knowledge. Otis ordered his editors to publish a “Statement on Behalf of Mrs. Leavitt” the next day. It was neither a correction nor a retraction. It read:

It was a mistake, [Mrs. Leavitt] says, to represent her as being personally acquainted with Mrs. Hollbrook (sic) and Mrs. Neirsheimer (sic) and as speaking of their adventures in the [Katherine] Tingley institution from personal knowledge of the facts. Mrs. Leavitt, in short, deprecates the mention of her name under any circumstances in connection with the mysterious doings at Point Loma and in conclusion ‘wishes to state that the ladies in question are not known by her and that she possesses no knowledge of the Universal Brotherhood affairs other than that which is the daily gossip of the neighborhood and the statements made through the various newspapers.’

The Times wasn’t the only newspaper to criticize Katherine Tingley and her community. New York newspapers mocked Tingley when they covered hearings in the fall of 1902 about a group of 11 Cuban children who were detained at Ellis Island on their way to the Raja Yoga School at Point Loma. Tingley had organized a relief committee for sick and wounded soldiers during the Spanish-American War and later recruited Cuban children—she called them ‘Lotus buds’–for her school.

The New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children argued before a board of inquiry that the Point Loma community was not suitable for children. The New York Tribune published a full-page story on the hearings, calling the Theosophical Society “a peculiar cult” and identifying Tingley as the “purple mother” for her flowing purple gowns. The article also claimed she owned a dog named Spots (sic) “in which was said to be reincarnated the spirit of a dead Theosophical leader.”

The Tribune article also quoted testimony claiming that donors to the school “will soon find out they are being duped” and that Tingley had established “a sort of paradise on earth where the children were taught to regard her as a superior being.”

After five weeks of deliberation, the board of inquiry recommended that the U.S. Immigration Commission should not admit the children. But Immigration Commissioner Frank P. Sargent reviewed the case and visited Point Loma to examine the conditions at the school. He was favorably impressed and ordered the children to be released. In the meantime, sporting goods magnate Albert G. Spalding, whose second wife was an enthusiastic Theosophist, chartered a launch to bring the children to New Jersey and then travel by train across the country to San Diego, where they were greeted by a grand procession.

In December, Tingley filed a lawsuit for defamation against Otis and the Times. It was to be the first of many courtroom dramas involving Tingley. She was represented by J. W. McKinley, a former Los Angeles city attorney and Superior Court judge whose clients included the Southern Pacific Railroad, and by Frederic R. Kellogg of New York City. The complaint charged that the Times had published Bartlett’s article “wickedly and maliciously and with intent to injure, disgrace and defame” Tingley. She sought $50,000 in damages, or about $1.8 million today.

The lawsuit didn’t deter the Times from publishing additional stories criticizing Tingley. One article repeated claims that Tingley was defrauding investors who paid to send relief supplies to Cuba. The Times also provided extensive coverage, with illustrations, of a lawsuit by a Chicago magazine editor, John J. Bohn, who claimed his two young boys were being held against their will at the Point Loma “spookery.” An article about the Bohn trial reported that Tingley “loaned her eminent and portly presence to the view of all in sight, and, like a fussy goddess, kept her little coterie of attendants dancing to her whims and theosophical obedience.” Bohn won custody of the boys.

The libel trial was delayed for months as Times attorneys filed a motion for a change of venue. They argued that it would be impossible to conduct a fair trial in San Diego. The paper, San Diego Magazine reported years later, had treated San Diego as a “municipal joke.” Otis’s chief counsel, Samuel Shortridge—who later became a U.S. Senator with Otis’s backing--conducted a survey of potential jurors and found that more than 6o percent of them “had nasty things to say about the Los Angeles Times and its owner.”

Superior Court Judge Elisha Swift Torrance, a heavily bearded man who regularly spit tobacco into a cuspidor beneath the bench, denied the motion. “The ill feeling against the defendant [is] not on account of the allegedly libelous article written against Mrs. Tingley,” Judge Torrance ruled,“ but simply because the defendant has systematically run down the town.”

The trial took place in the courthouse at Front and D streets, an Italianate building with a bell and clock tower, statues of four presidents, a 10-foot gilded statue of Justice and 42 stained-glass windows representing the states of the Union. Over the next two days, the attorneys selected a jury of 12 men, all but one of them farmers from the outskirts of San Diego. The jurors also sported a wealth of whiskers.

Testimony began on December 16, 1902. It pitted the charismatic founder of Lomaland against the blustery newspaper publisher. Tingley, 55, was the first witness.

The Times wasn’t backing off. On the third day of the trial, it published “A Point Loma Pome”:

Tingle, Tingle, little star

Oft I wonder who you are;

What you do that isn’t right,

Every blessed spooky night.

Tingle, Tingle little star

What a rotten sect you are

Better take a way back seat

With your brassy, bold conceit.

The defense case began with Otis, who testified that the Times-Mirror corporation was valued at about $1 million, about $36 million in today’s dollars. City Editor Andrews then testified about the assignment he gave Bartlett and said he had no “malice or ill will against the plaintiff.” Previously, he said, representatives of Lomaland had asked to him to print articles appealing for patronage and support and he felt the public had a right to know about the institution. The paper’s policy, Andrews testified, was “to use extreme care and accuracy and caution” when writing about an individual and to “get the truth, if possible.”

Bartlett then took the stand and testified that Mrs. Leavitt told him she was a friend of Mrs. Holbrook and had taken care of her after she left the colony. She also said she was a member of the “True School of Theosophy,” a rival of Tingley’s followers, and had become “so disgusted with the outfit at Point Loma” that she left San Diego. Mrs. Leavitt, he testified, said the colony was “a place of horror” and referred to the residents as “spooks.” Editor Andrews, Bartlett testified, had deleted some derogatory statements about Tingley from his article.

The Times lawyers tried to put Tingley on trial. On cross-examination, W.J. Hunsaker, one of Otis’s attorneys, noted that a number of news articles, and several San Diego ministers, had criticized her. Why, he asked Tingley, was the October 28 Times article so distressing?

“…The horror of children being starved in dungeons and all those horrible accusations were on my mind,” Tingley responded. “I could not eliminate them. They were false. They were horrible. I was in constant apprehension about the institution and the children. It was a nightmare. If I think about the article now, it still shocks me.”

Shortridge also cross-examined Tingley. “Are not your people sun worshippers?” he asked. “Do they not rise in the morning and go out upon the hill to worship the sun, after the fashion of idolaters?”

“No,” Tingley replied. “They do not.”

Otis’s attorneys also entered a deposition from Louis B. Fitch, a former bookkeeper at Point Loma, who repeated testimony about Tingley’s dog he had offered to the board of inquiry for the Cuban children. “Mrs. Tingley told me that Spot was a great deal more than a pet,” Fitch stated in his deposition, and that she believed the dog was the reincarnation of William Quan Judge, one of the founders of Theosophy.

“I believe I know,” Fitch said Tingley told him, “that Mr. Judge’s spirit entered into Spot at his death. Mr. Judge gave Spot to me at the time of his death and at the time I assumed the leadership of the Universal Brotherhood as his successor.”

The court struck most of his deposition from the record but the Times published the testimony under the headline: “Sacred Dog Spot Slips His Collar: Canine Possessed of Departed Man’s Soul: Fitch Deposition Hot Stuff.” Tingley, the article said, “fidgeted like an angry hen and indulged in indignant exclamations” as the deposition was read.

A San Francisco physician, Jerome A. Anderson, also testified on behalf of the Times. Anderson said he had first met Tingley in Boston in 1895. He later attended two-week conventions at Point Loma as vice president of the Theosophical Society. He described Tingley as a megalomaniac who acted on impulse and changed her mind frequently. Tingley, he testified, has an “unbounded belief in her own greatness, ability to rule, ability to manage everything…[and exercised] the highest form of self-conceit.” Her followers, Anderson added, “obey her abjectly” and her “influence over them seems to be hypnotic.”

Anderson also described midnight ceremonies conducted during the conventions. The adults, clothed in togas like ancient Romans, paraded with torches. They assembled to eat fruit that had “mysterious significance” and to listen to Tingley’s lengthy speeches. On one occasion, he said, she discussed “some marvelous displays of intelligence, supposedly, on the part of her dog.”

Anderson added credence to claims that the children were poorly fed. One of the colony’s doctors, he testified, wanted them well fed while Tingley “desired to have them at first starved because they could more likely kill out the lower nature in those children.”

Another witness for the Times, Lena Morris, who had served as a janitor for Tingley’s apartment building in New York City in the 1890s, testified Tingley “held herself out as a faith curer, a clairvoyant.” Tingley lived with her adopted daughter Florence. Tingley’s neighbors, Mrs. Morris said, “considered her a fraud and not very respectable.”

Otis’s lawyers also introduced a deposition from Irene N. Mohn of Los Angeles. Her husband, Dr. George Mohn, had brought their 7-year-old daughter to the school at Point Loma. Parents could only visit their children on Sunday afternoons.

“My daughter cried every time I saw her,” Mrs. Mohn testified in her deposition. She said her child’s hair and scalp were thick with dirt and her clothing was soiled. Tingley, Mrs. Mohn said, had told her that “mother love in me was very strong, but it was not good for the child, and her plan was to raise children entirely independent of that…that the mothers hold them back and the children could only go so far as the mothers went…She told me she was going to make them all workers for humanity and to go out into the world.” Mrs. Mohn had resigned from the Theosophical Society, saying she was “thoroughly disgusted.”

“I felt as though the whole thing was a scheme that Mrs. Tingley was working up and that she just wanted people that had money. I felt as though [the institution] was insane, devoid of all common sense in every respect.” (Years later, after her husband donated most of his later mother’s estate to the Theosophical Society, Mrs. Mohn successfully sued Tingley for exerting “undue influence” on her husband.)

Another witness testified that Tingley spoke of “secret masters who were hundreds of years old” in the Himalayas who communicated with her. Two children testified that they were not given sufficient food to eat.

Tingley was recalled to the stand and denied the claims against her. “I never considered that Spot was a remarkable dog,” she said. Her attorneys also called seven teachers from the Raja Yoga School, including Mrs. Neresheimer.

In his closing arguments on behalf of the Times, Attorney Shortridge relentlessly attacked Tingley.

“It seems that she snatched the sceptre and plucked the crown from the dead. At any rate, she claims to be a successor or somebody of Madame [Helena] Blavatsky or William Q. Judge—successor or self-appointed, she has marched with a stride up and taken her seat upon the throne and American citizens, men, are proud to bow before her and to do her bidding.”

Shortridge appealed to the Christian beliefs of the jurors. He compared Tingley to Mormon leader Brigham Young and argued that the plays she staged reflected the “paganism of ancient Greece.” Tingley, he argued, has exhibited “vindictiveness, cunning and craft” and has grasped for money throughout her life.

Judge Torrance effectively decided the case. “The publication, in all respects in which it is construed in the complaint, is libelous,” he said in his charge to the jury. He dismissed Shortridge’s oratory, noting that neither the “progress of Christian civilization [n]or the principles of the Christian religion are involved in the issues of the case.” He left it to the jury to decide the amount of damages. After three hours of deliberation, they awarded Tingley $7,500, about $271,000 in today’s dollars. She later claimed she had spent four times that in legal fees.

The rival Los Angeles Herald reported that Otis had been “worsted” by Tingley. “At last,” the Herald gleefully noted, “the self-styled hero of the Rubicon has been brought to bay—and by a woman. The stuffed warrior of paid write-ups, the brutal assassin of character, the would-be dictator of politics and society, the keeper of a ‘black list’ based upon his own treachery and unscrupulous ambition, has been halted in his campaign of calumny and abuse, rebuked by the courts and held up to scorn and ridicule—and by a woman…This is the man, the bold warrior, the newspaper dictator, the pen-and-ink assassin, who, compelled for once, against his will, to fight fair, has been worsted—by a woman, a mere woman.”

The Times countered by publishing opinions from other newspapers that came to its defense. It quoted the Ontario Record’s claim that Judge Torrance had erred by “continually ruling against a full revelation” of Tingley’s character. “If the press is debarred from exposing institutions which are supposed to violate the commonly-accepted code of public ethics and prey upon ignorance and superstition, it has lost a great part in its utility,” the Record wrote. The Times also reprinted an article from the Santa Ana Bulletin, which noted that the $7,500 verdict was being appealed and “that before Mrs. Tingley ever grasps any of those simoleons, she will have to make another run for the money.”

The Times’s appeals were denied and the verdict was finally upheld by the state Supreme Court in April 1907.

In the years that followed, Tingley returned to the San Diego courthouse as a defendant, contesting claims that she had manipulated wealthy donors to contribute to her colony rather than to their relatives. Perhaps the most bizarre case involved Harriet Patterson Thurston, the elderly widow of a Pennsylvania millionaire. In the summer of 1910, Tingley and Mrs. Thurston traveled across the country to Tingley’s childhood home in Newburyport, Massachusetts. Mrs. Thurston died there on July 21, 1910 at age 73. The cause of death was listed as pernicious anemia, a vitamin deficiency. Mrs. Thurston was cremated and her ashes returned to Point Loma. Shortly before her death, Mrs. Thurston had signed a will donating most of her inheritance to Lomaland. Her son contested the will and set the stage for another dramatic trial in San Diego Superior Court.

Tingley remained sensitive to criticism in the press and sought retractions whenever she believed she had been libeled. In July 1916, the Oakland Tribune published a magazine cover story about another contested will under the headline “Spalding Millions and the ‘Purple Mother.’ ” It was based on a lawsuit filed by Spalding’s heirs, claiming Tingley had defrauded them of their late father’s inheritance. Tingley countersued the family for defamation and demanded a retraction from the Tribune.

Nearly a year later, the newspaper printed a two-column apology at the top of its front page with the headline “The Truth About Katherine Tingley.” It reported that the magazine article was “inaccurate and misleading.” It added: “The Tribune, therefore, expresses to Madame Tingley and her associates its regrets that the article of July 16, 1916 was published. In order to counteract in a measure for the injury done by the publication of the said article, the Tribune cheerfully publishes this retraction and explanation.” The newspaper also reportedly paid Tingley $5,000 in damages and agreed to publish a positive feature about her in the magazine.

Tingley had muted the press. But the lawsuits continued.