After Joseph Smith was killed in June, 1844 in Illinois, Brigham Young claimed leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or Mormons. Young was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, the governing party of the church. He had been in the East raising support for Smith’s campaign for President of the United States at the time of Smith’s killing.

Smith and his followers had been attacked by mobs which felt threatened by the church’s growing economic and political power. Opponents also were alarmed by Mormon doctrine, which declared that other Christian denominations were illegitimate, and challenged their practice of plural marriage. Mormons were expelled from a succession of communities in Ohio. In Missouri, they were involved in a brutal war with citizens there, costing both sides lives and property. Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs ordered the state militia to drive Mormons from the state.

Mobs continued to attack the Mormons in Illinois after they established a community there in 1840 they called Nauvoo. But after Smith and his brother were arrested for destroying the printing press of a local newspaper which had criticized polygamy, a mob of 200 men shot Smith and his brother to death.

The violence against Mormons continued until Young negotiated a truce and led his followers on a 1300-mile exodus to Salt Lake Valley in the Utah territory. The United States had claimed the territory after its victory in the Mexican-American War and President Millard Fillmore appointed Young as Utah’s first territorial governor. Young supported the Mormon practice of plural marriage, defying federal efforts to outlaw it. "Any president of the United States who lifts his finger against this people shall die an untimely death and go to hell," Young said.

In 1857, Fillmore’s successor, President James Buchanan, declared that the Mormons were in "rebellion" and sent thousands of federal troops to Utah. Young declared martial law and instructed his followers to attack the federal army’s supply trains. He closed the trails to settlers headed west and forbade Mormons from selling them supplies. He also encouraged Indian tribes to harass wagon trains and to steal their cattle.

In the spring of 1857, a group of settlers from Arkansas headed through Utah on their way to California. The Mormons in Salt Lake City refused to sell supplies to the settlers and suggested that they should travel south on the Utah trail and rest their cattle at Mountain Meadows, which had good pasture. Yet rumors spread that the settlers were hostile to the Mormons; one Mormon accused them of poisoning a spring.

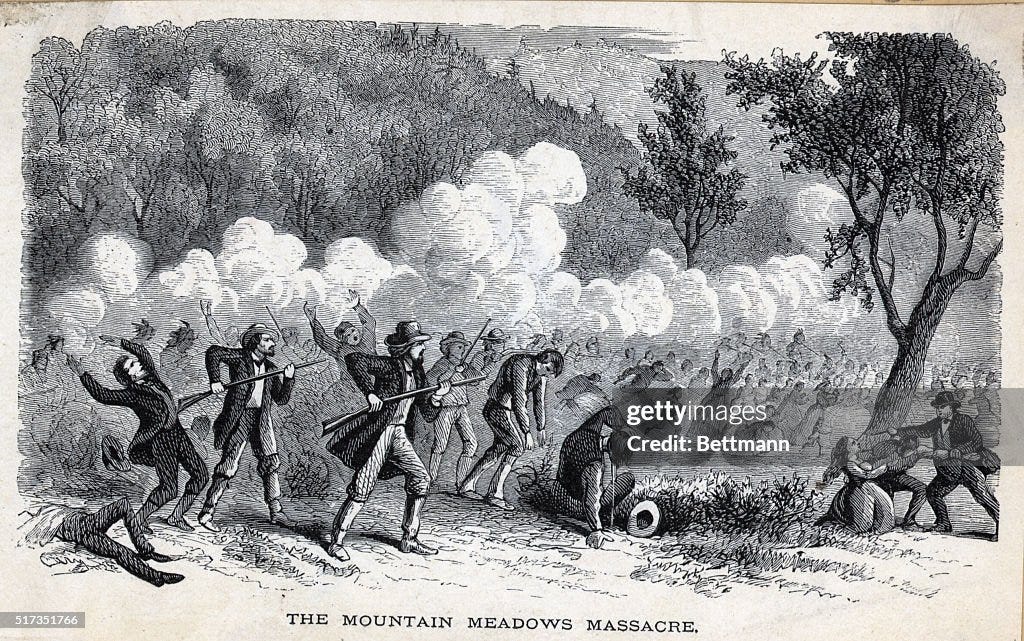

Members of the Mormon militia that was organized to fight federal troops decided to attack the settlers with the help of Paiute Indians. Several Paiutes and dozens of Mormons disguised as Indians attacked the settlers encamped in Mountain Meadows at dawn on September 7, 1857. The settlers encircled and lowered their wagons, chained the wheels together and dug a barrier of trenches around them. Seven settlers were killed and 16 wounded over five days of battle.

The Mormons feared that the settlers had seen white men attacking during the assault, undercutting their plans to blame the Indians. The leaders of the militia decided to kill anyone old enough to testify. On September 11, 1857, they approached the wagons with a white flag and told the settlers they had negotiated a truce with the Paiutes. The Mormons offered to escort the settlers safely back to Cedar City in exchange for turning their livestock and supplies over to the Indians.

The adult men were separated from the women and children and shot. The women and children were then ambushed and killed by militiamen who had been hiding in nearby bushes and ravines. The Mormons killed between 100 and 140 men, women and children and left the bodies to rot in the valley. The remaining 17 children were taken in by Mormon families.

Members of the militia were sworn to secrecy. They blamed the killings on the Paiutes and Mormon leaders concealed the truth of the massacre for decades. The Mormon war with the United States ended soon after the massacre and U.S. soldiers marched unopposed through Salt Lake City in June 1858. Young accepted a new governor for Utah and President Buchanan pardoned the Mormons for their "rebellion."

Jacob Forney, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Utah, a conducted an investigation of the massacre in the summer of 1859 and sent the surviving children of massacre victims to live with their relatives in Arkansas. Forney concluded that the Paiutes did not act alone, blamed local and senior church leaders and reported to the U.S. Congress that the mass killings were a "heinous crime."

The leader of the Mormon militia, John D. Lee, remained a fugitive until November 1874 and went on trial for murder the next year. His trial ended in a hung jury but Young struck a deal with the U.S. Attorney. In exchange for evidence confirming Lee's guilt, the U.S. Attorney agreed not to prosecute any other Mormons, nor implicate the church hierarchy in the massacre. Lee was convicted at a second trial in 1876 and executed in March 1877 at Mountain Meadows.

The Mormon Church didn't officially recognize responsibility for the attack until the early 21st century. On September 11, 2007, Church Elder Henry B. Eyring of the Quorum of the Twelve addressed a memorial service at Mountain Meadows.

"We express profound regret for the massacre carried out in this valley 150 years ago today, and for the undue and untold suffering experienced by the victims then and by their relatives to the present time," Eyring said. Church leaders were adamant that the statement should not be construed as an apology. "We don't use the word 'apology.' We used 'profound regret,'" church spokesman Mark Tuttle told The Associated Press.

Source:

“The Mountain Meadows Massacre,” The Mormons, American Experience, PBS, April 30, 2007

“Mormon Church Regrets 1857 Massacre,” Paul Foy, The Oklahoman, September 11, 2007