Today’s political and religious extremists, like those before them, attract followers and donors with their charisma and claims that they are being persecuted by those in power. They are mental predators, Robert J. Lifton writes, who “are concerned not only with individual minds but with the ownership of reality itself.” These leaders, Lifton adds, compress complex human problems “into brief, highly reductive, definitive-sounding phrases, easily memorized and easily expressed.”

In the late 19th century, spiritualist and social reformer Katherine Tingley emerged as the leader of a utopian cult that established a community in southern California.. She founded a school that separated young children from their parents and pledged to purify them of their imperfections. Tingley convinced her followers that she could create an ideal society free of uncertainty.

Tingley’s Theosophical Society, which lives on today, helped introduce a belief in karma and reincarnation into American popular culture. Members of the community rejected organized religion, followed strict diets and embraced homeopathic medicine. Yet Tingley was hated as much as she was admired, even within her own movement.

Was she a con artist who bilked millions from prominent American businessmen and other donors? A thin-skinned autocrat who filed numerous lawsuits against her critics? Or, perhaps at the same time, an innovator in educating children, promoting alternative medicine and contributing to music, theater and the arts?

“A Freakish Oriental Court”—the phrase one of her critics used to characterize her colony in San Diego—tells the story of the enigmatic Katherine Tingley. It also explores the social upheaval of the early 20th century and the corresponding growth of utopian communities and alternative religions. And it also shows the transformation of San Diego from a small farming community into a major port and military headquarters.

KATHERINE TINGLEY’S WAR ON THE PRESS (Part one)

Late in the morning of December 16, 1902, Katherine Tingley entered a San Diego courtroom to testify in her libel case against the Los Angeles Times. Tingley was the undisputed leader of the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society at nearby Point Loma. She hobbled in on crutches, escorted by two aides, and winced with every step as she approached her attorneys’ table. The Times had caricatured her as the “purple mother” for her flowing purple gowns, but on this day she wore an unflattering black dress, a blue jacket and a cream-colored hat. One of her aides produced a footrest for her leg, which she had injured in a fall down a steep flight of stairs at her residence. When he saw Tingley shuffle down the aisle, Times publisher Harrison Gray Otis whispered to one of his attorneys: “My goose is cooked.”

That afternoon, Tingley was called as the first witness. Her attorneys introduced into evidence a Times article from October 28, 1901. It accused Tingley, who had raised millions from wealthy donors, of starving women and children at her colony and treating them like prisoners. Her attorney asked Tingley if the article had affected her.

“I was very much shocked and suffered very much in consequence and have ever since that time mentally,” she testified. Tingley said she had severe mental distress and insomnia. “I was greatly incapacitated in my work,” she testified, “and not being able to do one-half as much as I had before this came.”

Otis’s rival newspaper, the Los Angeles Herald, reported that Tingley’s “voice is pleasant and softly modulated. A quiver was discernible when she testified to the mental suffering caused by the attack in the Times.” Two physicians who were treating Tingley for insomnia also testified.

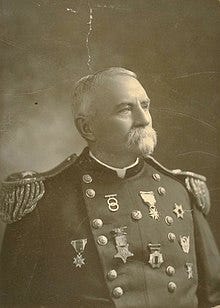

The Times and Publisher Otis had been targeting Tingley for years. Otis, 65, had contempt for powerful women, including Carrie Nation, Emma Goldman and Susan B. Anthony. Tingley and San Diego, the emerging city south of Los Angeles, were irresistible targets. Otis was a bellicose, union-busting Civil War veteran who kept an arsenal of shotguns in the newsroom and rode in a limousine with a hood ornament that resembled a cannon. He sported a walrus mustache and goatee. When he purchased a share of the Times and moved to Los Angeles, it was a small, unruly farming community. Otis relentlessly promoted his adopted home and relished opportunities to belittle San Diego.

The Times first targeted Tingley in a May 1899 front-page article. It claimed that instead of using donations to care for poor children at the colony, Tingley put the funds “to her own use.” In September 1900, the Times printed a lengthy feature story headlined “Weird and Wondrous City of Esotero. Strange Things are Going on in the Home of Mystery.” It described Tingley as an autocrat (“She-who-must-be-obeyed”) and “the most powerful and dangerous hypnotist in the world.” Other articles in the Times called the Point Loma colony a “crank institution” and identified Tingley as the “boss spook.”

Tingley, the paper wrote, toured San Diego on the raised back seat of an open carriage, like a queen on her throne. The Times provided extensive coverage of a lawsuit filed by William E. Griswold of Denver who claimed his 16-year-old daughter was being held against her will at Point Loma. In March 1901, under the headline “Rival Spookeries at San Diego,” the Times reported on an interview with Colonel Henry Steel Olcott, one of the founders of the Theosophical Society. (He was scheduled to speak at the Hotel del Coronado but moved his talk to the Fisher Opera House after Tingley threatened to call for a boycott of the hotel if he was allowed to speak there).

“We want nothing to do with the Point Loma institution,” Olcott told the Times, “but we do object to Mme. Tingley posing as the head of this great movement…I understand she has spent two or three hundred thousand dollars over there. She seems to have the faculty of gathering in money. I suppose she gets hold of a millionaire now and then and when she does she skins him.”

On a Saturday afternoon in October 1901, City Editor Harry E. Andrews handed reporter Lanier Bartlett a new assignment about Point Loma. Bartlett, 22, had joined the Times in 1900. He was born in Oakland, California and grew up in a Victorian mansion in Tustin. His father was a prominent banker and developer; his mother, Franklina Gray Bartlett, wrote short stories for Overland Monthly, a San Francisco magazine that published articles by Jack London and Mark Twain. She also helped found the Ebell Society of Santa Ana County, a club that promoted the advancement of women. Lanier Bartlett would later become famous as a novelist and screenwriter for more than 50 films.

City Editor Andrews told Bartlett he had just met with one of his sources, a local insurance solicitor, who had heard unusual stories from a Los Angeles woman about Point Loma. Andrews gave Bartlett a slip of paper with the address of a Mrs. M. Leavitt and two other names, Holbrook and Neresheimer. Mrs. M. Leavitt lived at 418 West Fourth Street, just a few blocks past the construction site of the Hotel Angelus, a luxury hotel that would open in late December. Bartlett went to her house on a Sunday afternoon.

Bartlett, a bespectacled young man with a part in the middle of his hair, identified himself as a reporter for the Times and said he was writing a story about the Point Loma community. Mrs. Leavitt said she wasn’t expecting him but nonetheless invited him inside. He interviewed her for several hours. She told Bartlett about the two women his editor had mentioned, a Mrs. Holbrook and a Mrs. Neresheimer, who, she said, had been rescued from the community. She asked him not to use her name in the story.

Bartlett returned home to eat dinner and then went to the newspaper office, a six-story granite building at First Street and Broadway that resembled a castle, to write his story. (Less than 10 years later, a labor union member planted dynamite in an alley near the Times, setting off a gas explosion that levelled the building, killing 21 people and injuring more than 100 others). Andrews edited the story, added Mrs. Leavitt’s name despite her request for anonymity and wrote the headlines:

OUTRAGES AT POINT LOMA

Exposed by an ‘Escape’ from Tingley

Startling Tales Told in This City

Women and Children Starved and Treated Like Convicts: Thrilling Rescue

Mrs. Leavitt was a member of a theosophical group that had split from Tingley’s society. Bartlett’s article identified her as a theosophist and reported she “has some startling things to tell concerning the practices of Catherine (sic) Tingley and her associates who conduct the Universal Brotherhood Homestead on Point Loma.” It continued:

Mrs. Leavitt seems to be thoroughly informed on two of the latest outrages perpetrated at the spookery, the cases of Mrs. Neirsheimer (sic) and Mrs. Hollbrook (sic), both well-to-do eastern women. Mrs. Hollbrook, the wife of a railroad man and a Freemason of the East, has been rescued from the roost on Point Loma by her husband with the aid of an officer and a gun and now hovers at the point of death from the abuse she says she received while confined in the ‘Homestead.’

During the daytime she was worked in the fields like a convict, forced to plant trees, hoe corn and perform all sorts of hard labor, and at night she was shut up in a cell and guarded as if she were a raving maniac. When her husband found what a trap she had fallen into he hurried here and took her out by force.

…Mrs Neirsheimer has been forcibly separated from her husband and is also in the Tingley clutches and is not allowed to speak to him. She is forced to live alone in a little tent in the grounds that surround the crazy institution. Armed men guard this place of horror, and, Mrs. Leavitt says, solitary confinement, hard labor and starvation are resorted to by Tingley managers as punishments upon those who disobey their iron rules.

…Mrs. Leavitt claims that through a strong hypnotic power, Catherine Tingley works her will on sensible people. The ‘Universal Brotherhood,’ or in other words, Catherine Tingley, is an off-shoot of the theosophic society, which became disjointed four or five years ago. Mrs. Tingley was formerly—the theosophists say—a common, dollar-talking spirit medium. She couldn’t agree with the theosophists so she branched off and set up her trap on Point Loma.

…Mrs. Leavitt says there is nothing taught at Point Loma but insane ceremonies; that the girls who are placed there to be educated are put to work at the most menial tasks, and each one kept separate in a guarded cell and forbidden to speak to anybody else, and that the poor little children are quartered in a miserable building some distance from the main institution and are continually on the verge of starvation.

…The children are never allowed to speak to anybody except when they are selling trinkets to the visitors who come to the gates. The young lady prisoners make fancy work, which they sell to strangers. Purple robes are worn by the women and a sort of khaki uniform by the men. On certain occasions a midnight pilgrimage is made by both men and women to a spot on the peninsula which is termed sacred ground. They go in their night robes, each holding a torch.

…Mrs. Leavitt alleges that gross immoralities are practiced at Point Loma by some of the disciples of spookism, as it is there exemplified and that such things should not be tolerated in a civilized community.

Bartlett clearly had a talent for fiction (and misspelling proper names). Neither Mrs. Holbrook nor Mrs. Neresheimer performed hard labor, nor were they imprisoned in cells. Mrs. Neresheimer taught music to children at Point Loma; her husband, a New York diamond broker, was a prominent donor and board member of the Theosophy Society. But there also were some grains of fact in his story. Residents of the colony did, in fact, work in the fields without pay. There were guards at the gates of Point Loma, but none were armed. The children did make products to sell to visitors and were, in fact, separated from their parents and instructed not to speak at meals or in their classes. They lived in canvas-covered huts, not cells. Residents did occasionally parade carrying torches in the middle of the night. But they were not convicts nor was the colony a “place of horror.”

In addition to the articles in the Times, Tingley confronted criticism from the local clergy. The Rev. Clarence True Wilson of San Diego’s First Methodist Church delivered a sermon in the summer of 1901 attacking Theosophy as a “substitute for the religion of Christ” and calling reincarnation, a core belief of Theosophists, a “fad.” On August 21, Rev. Wilson published a letter signed by 12 San Diego clergy, five pastors from nearby towns and a YMCA secretary, dismissing Theosophy as “the antithesis of Christianity” and labelling Point Loma as “a living Hades of immorality.”

Tingley challenged the ministers to a debate but they declined. For the next month, she booked speakers at the Fisher Opera House who defended Theosophy. Then, on October 20, she took the stage in a classical white gown to declare that San Diego and Point Loma had become the “centers of the contest between the good and evil forces of the world.” Tingley criticized the ministers as “enemies of human progress” who are “using their profession as a cloak for vice of the worst description.”

On October 29, the day after the Times published “Outrages at Point Loma,” Tingley vowed to sue the newspaper.

* * *

For thousands of years, San Diego has been home for Kumeyaay Native Americans who built villages in what is now the city’s Old Town. In 1542, explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo claimed the land for Spain. A later explorer named the area for the Catholic Saint Didacus, more commonly known as San Diego de Alcalá. Soldiers and missionaries established North America’s first Spanish fort and mission in San Diego in 1769 to colonize it and convert the Native Americans to Christianity, the first of 21 missions in what is now California. The Kumeyaay resisted the Spaniards' attempts to take their land, convert them and force them into slave labor. Spanish soldiers sexually assaulted Kumeyaay women and missionary staff whipped the men. In November, 1775, the Kumeyaay burned the Mission San Diego to the ground.

The region became part of Mexico from 1821-1846 after Mexico won its independence from Spain. The Native Americans continued to resist and raided the settlements. Thousands of Kumeyaay died in smallpox and malaria epidemics in 1827 and 1832. San Diego’s colonial population dropped to less than 150.

In 1835, a 19-year-old Harvard student, Richard Henry Dana, enlisted as a merchant seaman on board the Pilgrim, a ship collecting and selling animal hides. It sailed from Boston to California on the treacherous route around Cape Horn. In Two Years Before the Mast (1840)—a memoir that inspired works from Herman Melville and other seafarers--Dana described his arrival in San Diego, a motley settlement of about 40 dark brown huts with a barren landscape and ruins of the former Spanish fort. He also noted the town’s diverse population and its Mediterranean climate:

For landing and taking off hides, San Diego is decidedly the best place in California. The harbor is small and land-locked; there is no surf; the vessels lie within a cable’s length of the beach, and the beach itself is smooth, hard sand, without rocks or stones. For these reasons, it is used by all the vessels in the trade as a depot.

After the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), Mexico ceded present-day California, Nevada and northern Arizona to the United States. American negotiators insisted on including San Diego and its bay in their territories. California was admitted to the Union in 1850 and the city of San Diego was incorporated the same year. But within two years, the city was bankrupt.

Downtown San Diego was originally located at the foot of Presidio Hill, several miles from the bay. In 1850, William Heath Davis promoted a bayside development but for several decades it consisted of only a pier, a few houses and an Army depot. Late in the 1850s, San Diego became the western terminus of a stagecoach and mail operation that linked California to the eastern United States.

In the late 1860s, developer Alonzo Horton established a new town by the bay which became the heart of the city. San Diego remained small until the arrival of a railroad connection in 1885. The city’s population neared 40,000 by the end of the 1880s. But the real estate boom collapsed in the 1890s and the population dropped to less than 20,000. The city developed a reputation for lawlessness. A fabled gunfight in Moosa Canyon, just north of the city, reinforced that reputation.

The city welcomed Tingley and her followers when they arrived at the end of the 19th century. The San Diego Union published an eight-page supplement, with photographs, about Tingley and the colony she had established. Point Loma became a popular tourist destination and local businesses promoted it. More than 100 visitors a day paid for a guided tour of the colony with a Theosophist; it was a regular excursion for guests at the nearby Hotel del Coronado. Tingley also sponsored public performances at the Fisher Opera House and the Greek theater she had built, drawing thousands to see The Eumenides and The Wisdom of Hypatia.

The day after the Los Angeles Times printed “Outrages at Point Loma,” the San Diego Union published an article with the headline “Malicious and False.” It quoted Mrs. Neresheimer saying she and her husband were happily married and were comfortable residents at Lomaland.